Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the last few months, are chronically late to the theater and always miss the previews, or are deathly allergic to the smell of popcorn and artificial butter and so haven’t been to movies full stop, then you are almost certain to be aware that Disney’s cinematic retelling of Steven Sondheim’s classic musical Into the Woods is being released in a few weeks as a Christmas present to lovers of fairy tales and/or Johnny Depp everywhere. As a long time fan of Sondheim and of Into the Woods in particular my initial reaction was, ‘Really? Disney?’

This is NOT because I am a Disney hater. I live fifteen minutes from the park and got a report this week from Disney’s passholder services, who were ever so gently reminding me to renew, that I’ve visited the park no less than sixty or so times in the past couple of years. No, the reason for my reaction was that Sondheim’s musical is anything but your typical Disney faire. Very adult themes are addressed in the musical including rape, infidelity, child abandonment, stealing, lying, murder, and so on. None of the characters are classic heroes, many of the main characters die horribly, and the final song is basically the moral counterpoint to ole Jiminy Cricket’s suggestion that when you wish upon a star, “anything your heart desires will come to you.”

I realize that the musical Into the Woods is now over a quarter of a century old, having made its way onto Broadway in 1987, so many readers and moviegoers may not be familiar with the story. So, let us then dive into this steamy plot so you can get a sense of the many challenges that Disney faced in making a film for general audiences from Sondheim’s original work.

Spoiler Alert! It seems weird to give a “spoiler alert” warning on a story that has been around since Ronald Reagan was President, but before I begin to give you an analysis of Into the Woods I suppose I have to provide one. I want to dive into some of the themes and plots of the story, and really can’t do that without telling you about those themes and plots. If you have never seen the musical, first you are missing out — go to Amazon and rent it immediately, but second you should probably not read the rest of this article. If you really want to be surprised at how things turn out with Ms. Kendrick, Ms. Streep and Mr. Depp read this AFTER you’ve seen the movie. I’ll be here, I promise.

Act 1: Wishing and Hoping

First, you will read in many places that Sondheim was inspired to write his fractured fairy tale, which blends major elements and characters from Rapunzel, Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, and Little Red Riding Hood with an original storyline about a childless Baker and his wife (or as I like to call it, Hansel and Gretel in reverse) as a kind of post-modern meditation on Freudian themes within classic fairy tales, and on the dangers of ‘wishing.’ However, in a James Lipton interview published in the Paris Review in 1997, Sondheim disputes both of these points.

This is probably only interesting to psychology majors, or those of us who have been to way too much therapy, but with respect to whether Freudian analysis had a significant influence on the work, Sondheim answered, “Everybody assumes we were influenced by Bruno Bettelheim [for those of you not hip to mid-20th century psychologists, Bettelheim was a renowned child psychologist and writer that wrote extensively about Freud] but if there’s any outside influence, it’s Jung.” I only bring this rather obscure point up because the entire musical makes a lot more sense if you don’t view the actions of the characters through Freud’s lenses of life and death instincts like love, food, shelter and sex, but rather through Jung’s concepts about individuation and his archetypes: the father (the Baker), the mother (Cinderella and the Baker’s wife), the child (Jack and Little Red Riding Hood), the wise old man (the Baker’s father), the hero (the Baker and the princes), the maiden (Rapunzel), and the trickster (the Wolf). Now back to your regularly scheduled reading, in which I will attempt to summarize the intricate plot of Into the Woods in around 2000 words—and likely fail.

It is true that the dramatic action of the story begins and ends with the line “I wish…”, but on this point that the story is about the “dangers of wishing,”—which is highlighted in the tag line for the movie, “Be Careful What You Wish For,”—Sondheim himself does not (or I should say did not) agree that this really captured the main theme of the story. (Although it is a really good tag line.) Rather he said,

It’s about moral responsibility—the responsibility you have in getting your wish not to cheat and step on other people’s toes, because it rebounds. The second act is about the consequences of not only the wishes themselves but of the methods by which the characters achieve their wishes, which are not always proper and moral.

When I read this I have to admit that the entire story made a lot more sense (thank you, Mr. Sondheim). One of the problems I have with the idea that the moral lesson from Into the Woods is that you should be careful what you wish for is that the wishes the characters make are not absurd or obviously morally deficient. This is not The Fisherman and His Wife where the wife wishes ultimately to be God, or Rumpelstiltskin where the Weaver’s daughter wishes to spin gold from straw. The story of Into the Woods begins with three rather modest desires, the Baker and his Wife wish to have a child, Cinderella wishes to go to a ball (note not to get a prince, but just to experience a ball), and Jack wishes that his cow (and best friend) Milky-White would produce milk.

It is not in the wishes, but in how they go about securing their wished for desires that the trouble arises. To begin with, the Baker and his wife find out that the reason they can’t have children is that the Baker’s father (years ago) ran afoul of a neighbor witch who not only took from him his first-born daughter (Rapunzel), but also cursed his son (the Baker) with impotency. The witch informs them that she can reverse the curse if they will bring her four things before midnight of the third day has passed. These things are: “the cow as white as milk, the cape as red as blood, the hair as yellow as corn, and the slipper as pure as gold.” So, the Baker and his Wife go into the woods in search of these items.

Meanwhile, the other characters have also been forced or have chosen to go into the woods. Jack, he of the milky-white cow, has been forced by his mother into the woods to go sell their milk-less cow so they can eat. Cinderella has fled from her cruel stepmother and stepsisters into the woods to pray by her mother’s grave for a way to the prince’s ball. And, Little Red Riding Hood, as is her wont, goes skipping off into the woods to deliver bread to her grandmother.

The first of these characters to run up against the Baker’s desire for a child is Jack, who the Baker bamboozles into selling his beloved, and I mean beloved cow (listen to the words in Jack’s song “I Guess This is Goodbye”), for five beans he finds in the pocket of his father’s old coat. (Note, in the play the Baker is helped in this task and many others by a creepy old man who unbeknownst to the Baker is his long-lost and presumed dead father, who shows up quite regularly in the original work, but probably won’t show up in the movie at all since I haven’t seen anyone listed as playing him.) This is the first example of a character using immoral means to obtain their wish and it ends tragically, because the beans are magical and a giant beanstalk does grow from them and Jack does venture up the beanstalk and does steal from and ultimately kill the Giant (trying to get money to buy back his beloved, and again I can’t stress enough how much this kid loves his cow, Milky-White). In the second part of the story, this leads to the Giant’s wife coming down another beanstalk and taking her vengeance out upon the characters to tragic results.

The second character to run into the Baker is Red Riding Hood, who has just run into the Wolf who sings a song full of sexual innuendo (“Hello, Little Girl”) that I can only imagine is going to be heavily edited, as Disney actually got a little girl (Lilla Crawford) to play the role. I mean, the Wolf sings about “scrumptious carnality” for goodness sake, which I can only hope to heavens remains, because hearing Johnny Depp singing that line has to be a dream of nearly everyone on the planet. Anyway, after unsuccessfully trying to steal the cloak from the girl, the Baker pursues her only to be on the scene just in time to rescue her and her grandmother from the wolf by cutting them out of the wolf’s belly.

There is an interesting dynamic here between the Baker and his Wife, where in the first half of the story it is the Baker’s Wife who is pushing him to be ruthless (listen for the song “Maybe They’re Magic” about the beans), and then the Baker himself becomes ruthlessly obsessed with his quest to the exclusion of everything else. The experience with the wolf leaves Red Riding Hood completely altered. She now carries a knife and wears the wolf as a cape (having given hers to the Baker as a reward for rescuing her), and she sings about how “I Know Things Now.” Again, I’m not sure how much of Red Riding Hood’s performance will be preserved from the musical as there is certainly a sexual overtone in the original as she confesses that the meeting with the wolf scared her, “well, excited and scared” her.

If you thought things were confusing before, now the action comes fast and furious and mean and nasty. The Baker’s Wife runs into Cinderella, who has been to the ball (thanks, dead Mom) and isn’t sure the Prince is all he’s cracked up to be. While trying to understand why anyone wouldn’t want to marry a prince, the Baker’s Wife discovers and then tries to steal one of Cinderella’s slippers. Jack returns with gold from the beanstalk and tries to buy back Milky-White from the Baker, but the Baker’s Wife has lost the animal in her pursuit of Cinderella. Rapunzel has been discovered and repeatedly “visited” by a different prince and by the Baker’s Wife who rips out a chunk of her hair. (And, before you ask, yes there are two nearly identical princes in the story and their song “Agony,” in which they try to one-up each other on how tragic their love-lives are, is hilarious.)

Not so funny is that the Witch discovers that Prince (we’ll call him #2) has been visiting Rapunzel, which leads to the Witch singing her song “Stay With Me,” which from the trailer is going to be a highlight of the movie. When Rapunzel refuses to stay the witch cuts off her hair and banishes her to a desert where she gives birth to twins. Oh, and the Witch blinds Prince (#2) also—very nice. (By the way, all of this nastiness with Rapunzel is very much in keeping with the way the Grimm Brothers originally told the story.) Meanwhile, Jack and Red Riding Hood run into each other and Red Riding Hood goads Jack into returning to the Giant’s realm to steal a golden harp. Somewhere in all this Milky-White dies and is buried. (Whew!)

As the third midnight arrives and we close the FIRST part of the story (yes you read that right we are only half-way done), Cinderella leaves one of her golden slippers behind for the Prince (#1) to find, which he does. The Baker’s Wife manages to steal the second of Cinderella’s slippers. The Baker, the Baker’s Wife and the Witch manage to resurrect Milky-White and create the potion, which restores the Witch’s beauty and thus lifts the curse from the Baker. Jack, who is now exceedingly wealthy having killed the Giant and stolen most of his riches, gets back his now milk-producing Milky-White. And Cinderella is discovered by and then weds Prince (#1).

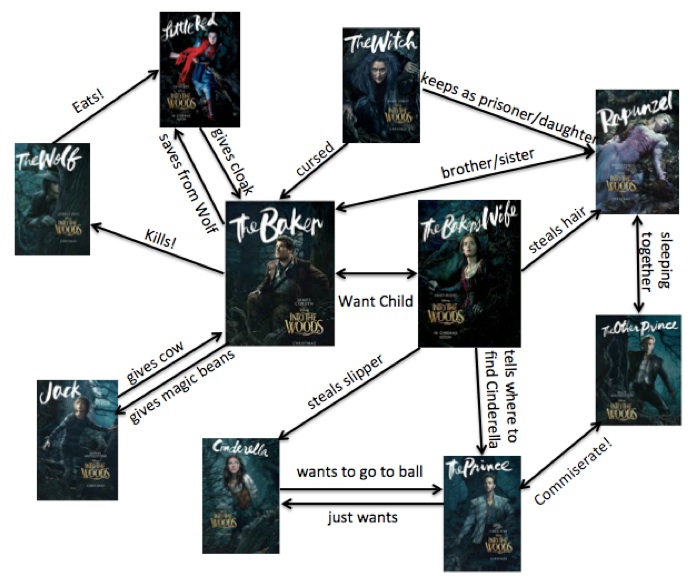

I have diagramed all this action, reaction and interaction below for your convenience. (Click to enlarge.)

Simple, right?

Act II: The Truth of Consequences

At the end of the first part of the story then everyone is presumably happy. They each have fulfilled their wish, and can now live happily ever after. The Baker and his wife have a child. Cinderella is living literally like a queen with her Prince (#1). Jack has his health, his wealth and his cow. Red Riding Hood is alive and has a grandmother she can visit without having to worry about the Wolf ever again. Only Rapunzel and the Witch can be said to be unhappy. Although the Witch has her beauty back, she has lost Rapunzel forever. Meanwhile, Rapunzel has her children and has found her Prince (#2) and cured his blindness, but having been locked in a tower all her life is plagued by fear and anxiety. And, there is another shadow looming over all of this happiness—and it’s a big shadow.

Remember that Giant Jack killed? It turns out he had a wife, and the Giantess is angry. She comes down a second beanstalk that grew from that last bean of the Baker’s and starts wreaking havoc. She wants vengeance and demands the people hand over Jack, which everyone is willing to do except the one person that knows where he is—Jack’s mother. During a confrontation with the Giantess, Rapunzel, who has been driven pretty much insane by the Witch’s treatment of her and the stress of being a mother, rushes towards the Giantess and is crushed.

It is my understanding, from Variety, and other such fine publications, that this will not happen in the movie. I have no idea, and sometimes it seems like Sondheim has no idea what is actually going to happen in the movie. In June he gave a number of answers to the question of whether the story had been “Disneyfied,” at one point saying, “You will find in the movie that Rapunzel does not get killed,” only to backtrack five days later. There is a new song, “Rainbows,” that may or may not make it into the final cut that is or was to have been sung by Ms. Streep’s Witch, which may address this plot change. In the end your guess is as good as mine, but in many ways Rapunzel’s death is the most poignant and important to the story. She was a true innocent, and the brutality and suddenness of her ending is the first moment where the rest of the characters begin to realize the real and terrible consequences of their actions.

Whatever happens there, if the movie sticks at all to the plot of the musical characters will begin to drop like flies. Jack’s mother is killed by the Prince’s steward for arguing with and infuriating the Giantess. Red Riding Hood’s grandmother is killed in another attack by the Giantess and her mother goes permanently missing. The Baker’s Wife—who while out looking for Jack runs into Cinderella’s prince (#1) and has a brief roll in the woods with him, by which I mean they have a roll in the hay, by which I mean they have sex—with the immediacy of horror film morality is thereafter crushed by a tree that the Giantess knocks over. (Note, Sondheim has also had public debates with himself about whether the Baker’s Wife’s liaison with Prince (#1) will make it into the film.)

So, we are left with Cinderella and her Prince (#1), the Baker, Jack, Red Riding Hood, the Witch, and an enormous body-count. There is a moment (“Your Fault”) where they turn on each other, each claiming that the death and destruction is someone else’s fault in an endless loop of pass the blame. The Baker decides to leave his child with Cinderella and run away, and it looks for a moment like no one will end up happy.

But, in a magical moment that is pure Sondheim, each comes to a place of wisdom about how they contributed to what happened. The Witch sacrifices herself to give the other characters an opportunity to defeat the Giantess. And, in the end, they do by working together. Cinderella leaves her inconstant Prince (#1) and decides to stay with the Baker and his baby, and the Baker decides to take in Jack and Red Riding Hood. However, this is not the saccharine sweet ending of most Disney movies. Each of the characters has lost someone. Jack has lost his Mother. Red Riding Hood has lost her grandmother. Cinderella has lost her Prince (#1). The Baker has lost his wife. Still, one imagines that they will live, if not happily ever after, certainly much wiser ever after, and they will not be alone.

Throughout the story the characters leave us with many morals, from the thought provoking, like the witch proclaiming, “Careful the things you say children will listen,” to the comical, like Jack’s Mother explaining, “Slotted spoons don’t hold much soup.” But, the one that always strikes me comes in the final few choruses of the reprise of the song “Into the Woods” at the end of the second act where the whole cast sings:

“You can’t just act,

You have to listen.

You can’t just act,

You have to think.”

Ultimately, if Disney’s version of Into the Woods can convey that message then, even if it does allow Rapunzel to live and even if it turns down Depp’s sexiness so the Wolf will be less lascivious and even if it cuts out the adultery so the Baker’s Wife will be more chaste, it will still be a film worth seeing. I suppose in the end I will leave my judgment to the story and performances on the screen, but I cannot say that I am not worried. I just can’t help think that, despite Disney’s obvious desire to adapt Into the Woods, perhaps they should have heeded their own warning to “Be Careful What You Wish For.”

Jack Heckel is the writing team of John Peck, an IP attorney living in Long Beach, CA who is looking forward to the upcoming release of Once Upon a Rhyme, and Harry Heckel, a roleplaying game designer and fantasy author, who is looking forward to the publication of Happily Never After.